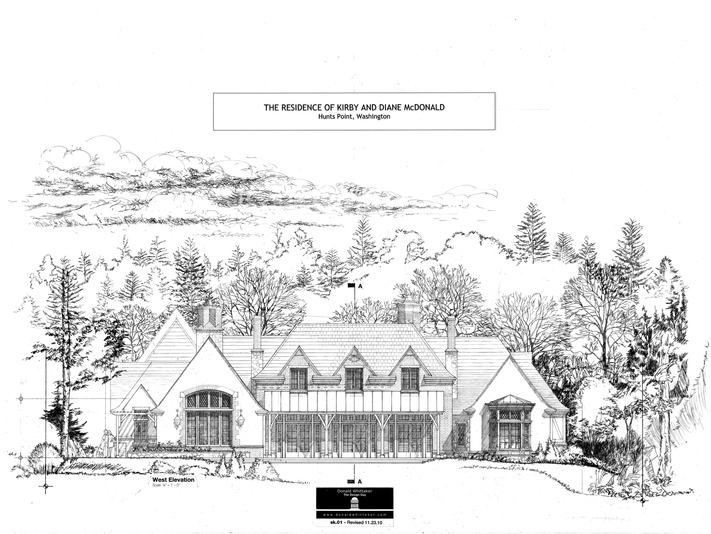

This Country Manor on Hunts Point, required an exceptional team of professionals to execute, and none more important than its general contractor Claremont Construction led by the project manager and general partner, Adam Greisz. The grounds of this Country Manor, created by landscape architect Richard Hartlage, recall the green serenity of an English country estate where a winding drive and footpaths wind under magnificent specimen trees and end at casual gardens. Massive trunks, three-lobed pointed leaves, and cherry-sized seed clusters distinguish trees that frame the west lawns. A beautiful stone wall surrounds the separate owners and guest's motor courts and unites the manor house with detached guest quarters above additional garages.

Service

Planning and design

Client

Kirby and Diane McDonald

Location

Hunts Point, WA

A Country Manor

Black Tie Optional

Neoclassicalmanor

By D. Whittaker

The front door frames the view of the two-story entry hall. The library is on the left axis, flanked by the staircase. The Grand Parlor juxtaposes the axes, and the dark blue waters of Lake Washington lay dead ahead and beyond. This unique home will undoubtedly stand the test of time because of the quality of materials employed, the mastery of its construction, and the neoclassical design will be proof enough for that.

The term stately home is subject to debate and avoided by historians and other academics. As a description of a country house, the term was first used in a poem by Felicia Hemans, The Homes of England, originally published in Blackwood's Magazine in 1827. In the 20th century, the term was later popularized in a song by Noël Coward, and in modern usage, it often implies a country house that is open to visitors at least some of the time.

In England, "country house" and "stately home" are sometimes used vaguely and interchangeably. However, many country houses such as Ascott in Buckinghamshire were deliberately designed not to be stately, and to harmonize with the landscape, while some of the great houses such as Kedleston Hall and Holkham Hall were built as "power houses" to dominate the landscape and were intended to be "stately" and impressive. In his book Historic Houses: Conversations in Stately Homes, the author and journalist Robert Harling documents nineteen "stately homes"; these range in size from the vast Blenheim palace to the minuscule Ebberston Hall, and in architecture from the Jacobean Renaissance of Hatfield House to the eccentricities of Sezincote. The book's collection of stately homes also includes George IV's Brighton town palace, the Royal Pavilion.

Villa Diana consists of 9,800/SF of interior conditioned space. The home is gated and private; the baronial public rooms with 24-foot coffered ceilings and the extensive use of white oak herringbone plank floors allow this neoclassical Palladian Villa to stand out through its quality, luxury, and elegance.

Arriving at the domain, one passes through a pair of forged iron gates that lead to gentle access leading you to the guests and owners' separate motor courts and garages. The colossal and darkly stained antique entry pair doors are 4.5 inches thick with multiple panels, massive hardware, and iron scrollwork with fields of leaded glass.

Beginning at the front door foyer, Lake Washington is veiwed through a bisecting corridor and through the two-story great hall designed as a perfect square with 24' coffered ceilings, with a matching pair grand mantels that flank the south-facing wall, which, in turn, presents a significant steel and glass system bleeding interior space directly onto a magnificent stone and tile terrace.

The house features five bedrooms and six bathrooms, all with garden and lake views and privacy that rarely a drape will need to be drawn. There is a hidden owner's motor court facing east which provides access to a three-car garage.

Inside the home, one can enjoy an extensive wine cellar, a gourmet kitchen with French limestone counters that will make any mogul scream, "C'est Magnifique!"

The Villa occupies a 44,000/SF lot which uniquely provides 320' of waterfront, multiple docks, a sandy beach, and perfectly cultivated and landscaped; the estate has many wonders in store, setting a new standard for elegant living. With a beautiful yard covered with patios, lush green grass, fountains.

As surveyor of the Royal Works from 1615-1642, Inigo Jones introduced Palladian Classicism to a limited circle, but it did not become popular in Britain until the following century. Britain was so slow to wholeheartedly embrace the Italian Renaissance that by the time Jones emulated Andrea Palladio, Italian architects had passed from pure Classicism through the more theatrical Mannerism towards Baroque. These latest Italian styles filtered into British architecture more quickly, with the result that Palladianism, in general, follows Baroque in Britain.

There are no written terms for distinguishing between vast country palaces and comparatively small country houses; the descriptive words, including the castle, manor , and court, provide no firm clue and are often only used because of a historical connection with the site of such a building. Therefore, for ease of explanation, Britain's country houses can be categorized according to the circumstances of their creation.

"Consider the momentous event in architecture when the wall parted, and the column became.' ~Louis Kahn

That’s my buddy, my best friend, and my companion, Axel. And that’s the UW Huskie row team practicing in the background, Sammamish Slough – August 2021.